The White Album

Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like bushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true. The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled.

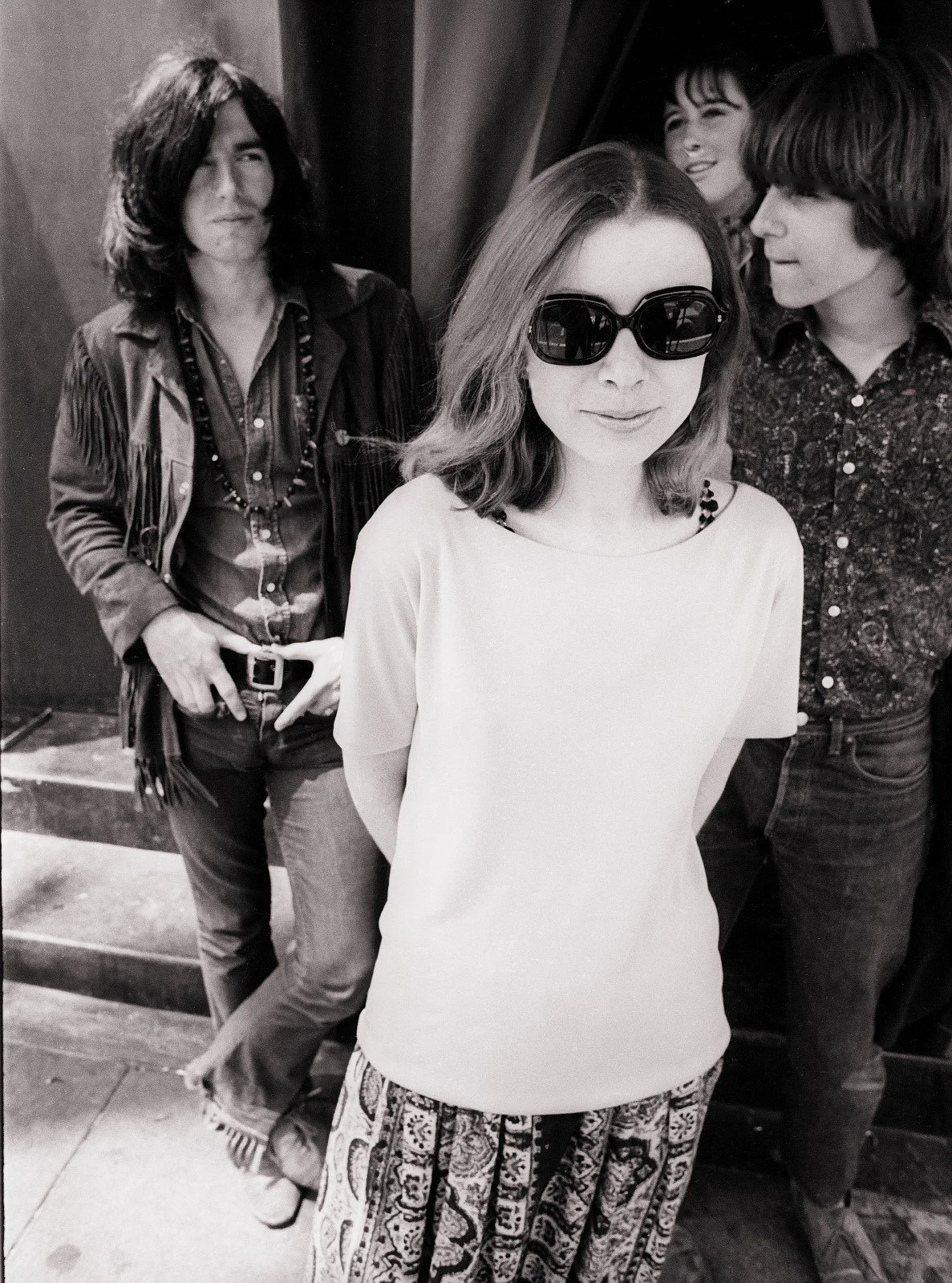

© Julian Wasser

JOAN DIDION, HOLLYWOOD, 1968.

The White Album is an essay by Joan Didion published in 1979, completed by some of her best columns published at the time in Life, Esquire, The Saturday Evening Post, The New York Times or else The New York Review of Books.

A proponent of New Journalism, in the manner of a Tom Wolfe or a Norman Mailer, she writes in the first person, the style is sharp and the details precise. She doesn't bother with context. Insolently subjective, she gives up here her most intimate thoughts, which makes the book all the more powerful as it is ultimately very personal.

The text is made up of disjointed flashbacks, where like in an editing room, the rushes overlap endlessly, as if to better transcribe the apocalyptic essence of the end of the Sixties in Los Angeles, where nothing seemed to make sense or follow any intelligible narrative thread. America itself was in the process of falling apart and losing all its bearings, Joan Didion delivered to us a time capsule in that regard.

On September 23, 1967, her article “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” appeared in The Saturday Evening Post. It opened with the poem The Second Coming (1919) by William Butler Yeats.

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world . . .

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand . . .

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Verses that look like epitaphs for this report on youth culture and their drug use produced in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, and whose story ends with Susan, this five-year-old kid with odd white lips. For the past year, her mother had been fueling her by acid and peyote, Mind Expansion dictates. Already the seedy overrode utopia for these children of the American Dream.

She used it as the title of her second book published in 1968, which gathered other of her articles that came out in the press. In the preamble, she described the necessity for her to accept “disorder” (“it would be necessary for me to come to terms with disorder”). This time, at random of ordinary violence responded an internal agitation. Her body gave way the year she was yet named “Woman of the Year” by the Los Angeles Times.

By then, Joan Didion, the girl from Sacramento, an English Literature graduate of the University of Berkeley in 1956, went through New York where she earned her stripes at Vogue for almost eight years, and where she got married to the writer John Gregory Dunne. Now based in California with their two-year-old daughter Quintana, the couple collaborated for several newspapers and worked on various scripts for television and cinema. As part of Hollywood's crème de la crème, they happened to be frequently quoted in the “Great Life” section of the Hollywood Reporter, just like Bianca Jagger, Paul Morrissey or Linda Ronsdadt.

© Julian Wasser

JOAN DIDION, JOHN GREGORY DUNNE AND QUINTANA ROO DUNNE, HOLLYWOOD, 1968.

Their house on Franklin Avenue was located in a former swanky Hollywood neighborhood now slated for demolition. Huge unfurnished 28-room homes which once served as embassies and consulates were now rented by the month. Very popular among music bands, they also encouraged the establishment of communities of all kinds, a most eccentric area.

Joan Didion's home was a theater stage in itself. One could bump into Janis Joplin coming to have a “glass” of brandy-and-Benedictine after a concert, a babysitter who told her she saw death in her aura, a so-called delivery man from Chicken Delight or a former classmate who, after 14 years, resurfaced as a private detective. It was not uncommon for her to receive crazy phone calls from people wanting to save her through Scientology or enroll her in drug deals. It was a strange time, and yet few things managed to surprise her.

She mentions for a moment the case of Jody Fouquet, a symbol of that ordinary violence, totally arbitrary and without any apparent logic. At 7:15 a.m. on October 25, 1969, Thomas Craven of the California Highway Patrol went to Jody Fouquet’s assistance, a five-year-old girl, abandoned by her mother in the middle of the highway and who spent the entire night on the median strip. Betty Lansdown Fouquet, 26 years old and mother of seven children, claimed for her defense to have committed this act in order to save her daughter's life. Her husband, Ronald Fouquet, 31 years old, had been threatening to leave her to die in the desert. Betty had four children from a first marriage to Billy Joe Lansdown. Ronald happened to be Jody's stepfather and the father of her last three children. A violent person, who regularly rained blows on the whole family.

During this case, the court of law realized that one of the children was missing, little Jeffrey was nowhere to be found. Betty then confessed. She told how, three years earlier, in 1966, Ronald beat to death the little child, who was himself five years old at the time. She described a jealous Ronald who could not stand Jeffrey being the son of another man. The police had indeed discovered the body of a little boy at the foot of a dike, but his advanced state of decomposition did not allow him to be identified. After his death, Jeffrey's body was packed into a modest suitcase. She, her husband, and three other of her children drove into the desert where Jeffrey was simply dropped from the car.

Joan Didion also dwells on the murder of actor Ramón Novarro, then 69 years old. A world star of silent movies since his role in Ben Hur (1925), he was brutally murdered at his home in Laurel Canyon, not far from where she lived.

After Bob Dylan and the Greenwich Village, Laurel Canyon had become the epicenter of the rock revolution. From New York to Los Angeles, the music scene set up home in the West. Everyone moved to Laurel Canyon. Actors, musicians, artists formed a most open community where freedom and creative competition prevailed. In the neighborhood: the Rolling Stones, Frank Zappa, Joni Mitchell and Graham Nash, Neil Young, David Crosby, the Byrds, the Turtles, the Doors, Buffalo Springfield..., to name a few.

There was a lot of freedom. There was a lot of drugs. There was a lot of beautiful women. There was a lot of good rock n’ roll being made. It was a fabulous time.

(Graham Nash, guitarist of Crosby, Stills & Nash, in episode 10: « Sex, Drugs, and Rock N’ Roll (1960-1969) » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

And yet, on October 30, 1968, the Ferguson brothers ended up shattering this idyllic setting. Nine days earlier, Thomas Ferguson, 17 years old, showed up in Los Angeles at his brother’s house, Paul, 22 years old, whom he had not seen for two years. He had just escaped from a reformatory in Illinois. The two brothers were not really close, as they only grew up for a short period of time under the same roof.

Coming from a family of ten children, the father was a steeplejack and dragged his family from one place to another, between Alabama and Illinois. When he wasn't away for weeks, he preferred to indulge in alcohol rather than provide for food or rent. Paul claimed to have prostituted himself since the age of 10 to meet his family’s needs. At 14 he definitely set sail. Hitchhiking, he worked on various ranches in Mexico and Wyoming. At 15, he joined the army, lying about his age. He was honorably discharged the following year.

As for Thomas, he went from juvenile detention centers to stays in psychiatric establishments. He ran away at the age of 15. When Thomas arrived at his home, Paul had been married to Mari for three months. The two lovebirds met via Larry Ortega, Mari's brother, a prostitute who played pimp from time to time. Paul just got fired from his last job and he and Mari were penniless. The tension was mounting and Mari left to live with her parents for a while. Paul then decided to arrange a deal for “Tommy”. He therefore called Victor Nichols, a real estate developer with links to the world of prostitution, and he was given the telephone number of a man named Novarro.

The Sixties were far from being a time of tolerance and the actor lived his homosexuality in a hidden way. He often called on escorts. This is how, by the coincidences of life, the Ferguson brothers found themselves at his house, on that eve of Halloween.

After years of alcoholism, Novarro's career had long been on the decline. That did not prevent him from wanting to impress the Ferguson brothers who probably thought they had stumbled upon the goose that lays the golden eggs. With the help of alcohol, things got out of hand. Paul and Thomas expected to find 5000 dollars; they went back home with 20 dollars in the bag and left a swollen, naked, bloody corpse, tied to an electric cord. The autopsy revealed that Novarro had choked on his own blood due to multiple traumatic injuries to his face, neck, nose and mouth.

JOEL MCCREA AND RAMÓN NOVARRO IN THE WESTERN THE OUTRIDERS, 1950.

About the summer of 1968, Joan Didion would say: “an attack of vertigo and nausea does not now seem to me an inappropriate response.” And for good reason, to ordinary violence was responding political violence. In barely two months, America successively lost two of its greatest leaders: Martin Luther King, assassinated on April 4, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee, and Bobby Kennedy, assassinated on June 5, 1968 (he died the next day) in Los Angeles, after winning the Democratic primary in California. And Lauren Bacall to let out this cry:

I mean, what happens to the country? I mean, you wonder if it’s worth saving, you know. What is it? What’s left of this country?

(Episode 8: « 1968 » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

But we have to rewind the movie to understand to what extent the poison of violence had permeated all strata of American society, being testament to a general crisis of political and moral values that was shaking America in the Sixties.

On November 8, 1960, John Fitzgerald Kennedy won the presidential election against Republican Richard Nixon, who was none other than Eisenhower's Vice-President (1953-1961). The Harvard Dream Team, the Best and Brightest, hence acceded to the White House at the start of 1961. Kennedy was young, barely 43 years old. Beautiful, brilliant, dynamic, in the spirit of the times, he embodied a breath of renewal and hope, in an America where one in two Americans was under thirty. This was a president who looked like them. He “became the hero of all those who remained convinced that America, through its intelligence, its resources and its quality of life, would constitute a model which would peacefully demonstrate the superiority of its system and its institutions over the barbarity of communist regimes.[1]” In short, the wish for a fairer, less puritanical and more humanist America.

Many also expected him to confirm Black people Civil Rights through legislation. “In the Southern states, Black people were still considered second-class citizens. Since 1896, their social life had been governed by the formula “separate but equals”. The founding principle of all apartheids.[2]” They did not have the right to vote, contrary to the Northern states, and in addition to being exploited, were often victims of lynchings and summary executions. Thus, the populations of the industrial cities of the North, youngsters, Black people, women, students and intellectuals were behind Kennedy. But make no mistake, with a record turnout and a gap of barely 113 000 votes with Nixon, that being 0.07%, America was well and truly cut in two.

As pledges to the Republicans, Kennedy kept in office Allen Dulles and Edgar Hoover, respectively heads of the CIA and the FBI, even if the latter remained totally assimilated to the Cold War and McCarthyism. Suffice to say that the time of schemes was not about to end.

The President also had to deal with the “Dixiecrats”, these Democrat parliamentarians from the Southern states, segregationists and for the most part ultraconservatives. Originally, Dixie or Dixieland, was the nickname given to the territory covered by the former Confederate States of America, namely South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas, to which were added four other secessionist states, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina. They were sometimes associated with the equally slave states that were West Virginia, Missouri, Kentucky and Maryland, but which them remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War (1861-1865).

To understand correctly, on this year of 1961, all the governors of these states, without exception, were Democrats. “No Southerner would have condescended to vote Republican, the party of Lincoln and Grant, of Emancipation and Reconstruction. Permanent paradox of the Democrat Party, libertarian and progressive in the North, segregationist and conservative in the South.[3]” Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant were both Republicans. Respectively 16th President of the United States (1861-1865) and 18th President of the United States (1869-1877), one proclaimed the abolition of slavery in 1863 when the other commanded the Unionist armies during the Civil War. We then understand better the old overtones and the aversion to the Republican Party still present at that time. However, it was in these Democrat lands that white supremacists were acting without any qualms in complete impunity and where the all range of segregationist laws called “Jim Crow” applied. Black people obviously wanted to definitively shake off the shackles of domination and for the decisions of the Supreme Court to finally apply in these Southern states.

To help him, Kennedy would rely on the second on the Democrat ticket, Lyndon Baines Johnson, a Texan and wise politician, he was also leader of the senatorial majority. Even if at that moment, the President found himself his hands tied, not having a “liberal” majority in Congress; therefore, Black people had yet to be patient and wait at least for the midterms of November 1962 to take place to witness any progress in the territory of Civil Rights.

To tell the truth, on this year of 1961, JFK's attention was rather focused on the Soviet Union. In line with the doctrine of “containment” (keeping communists within their territorial boundaries) stated by Truman (President of the United States from 1945 to 1953) whose logic led Eisenhower to support the bloodthirsty dictatorship of Batista in Cuba or else the despotic regime of Diem in South Vietnam, Kennedy took a very dim view of the bridgehead offered to the Soviets by Castro about sixty miles from the American coasts.

After the Bay of Pigs fiasco on April 20, 1961, yet an operation he gave the green light to, the Vienna Summit of June 3 and 4, 1961, between John Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev ended in failure. That meeting aimed to attempt to appease tensions between the two blocs. However, Soviet nuclear tests resumed on August 5, and at the end of August the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union finished the construction of “his” Berlin Wall. Tension kept intensifying with the Russian leader, peaking during the second Cuban crisis, where from October 16 to 28, 1962, we verged straight on the Third World War, before Khrushchev finally packed up his nuclear missiles.

The conflict could have meant mutual destruction, carrying off the entire planet with it. The idea of a nuclear war was on everyone's minds and was far from being an abstract notion for the Americans who came out of this crisis traumatized. Consumer society dictates, air raid shelters became really popular, bunkers being more and more sophisticated. As for the young Americans, since Truman and the establishment of "school drills", they were periodically subjected to simulated nuclear attacks where they were taught to hide under their school desk like Bert the Turtle. So nothing that felt reassuring. Kennedy's composure in this matter was in any case remarkable and allowed him to restore his image internationally. So, in the absence of waging a conventional war, the competition between the two powers took place in space.

Since the Beep-Beep of October 1957, the sound of the signal transmitted by the Russian Sputnik, the first satellite put into orbit by human technology, 560 miles above our heads, American space science was behind the times. On April 12, 1961, Russian scientists sent this time into orbit the first man into space. Yuri Gagarin carried out a 108-minutes flight aboard the Vostok 1 spacecraft. That was it for Kennedy, who appeared before Congress on May 25, 1961. He proposed an increased budget of 7 to 9 billion dollars in order to finance the conquest of the Moon. This was the birth of the Apollo project. The goal: to send and safely return a man to the Moon within the next decade. It received the support of the overwhelming majority of Congress.

Truman had ordered the resumption of research and testing of the H-Bomb, the thermonuclear atomic bomb; Eisenhower in his end-of-term speech oddly warned against the uncontrolled militarization of society. We were right out in it. Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, a new military budget was presented before Congress. On a considerable rise, it was supposed to be added to NASA's budget for the Apollo project. The proposal was passed without difficulty. All this money, which must be counted in billions of dollars, could have been used to finance the long-awaited social and educational reforms, in a country where one in five Americans, so 20% of the population, still lived below the poverty line. However, with unemployment reaching a record rate of 8% and growth below 4 points, the new administration was choosing to respond to the recession with a massive injection of military credits. From capitalism to economic planning, the line became increasingly tenuous.

On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court declared segregation in schools unconstitutional. Nine years later, George C. Wallace, the governor of Alabama, was still trying to ban the enrollment of two young Black students at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. Vivian Malone and Jimmy Hood, both twenty years old, were to their detriment, the heroes of a saga that kept all of America on tenterhooks at a time when almost 88% of the population owned a television set.

On June 7, 1963, Governor Wallace ordered the presence of 500 Alabama National Guardsmen near the university. On June 11, 1963, the situation becoming untenable and not wanting to repeat the experience lived by James Meredith, this Black student and former US Force, for whom it took three months and the presence of 400 federal agents to finally be registered at Oxford University in Mississippi, and whose riots cost the lives of two people in 1962, President Kennedy finally used his power. Paying no heed to the old feud over state law, he federalized Governor Wallace's troops, which aimed to place them directly under his command. A clear message was sent, no one was above the law and from now on the fight for Civil Rights would become the top priority of the Kennedy administration.

Until then, he and his brother Robert Kennedy, the brilliant Attorney General, had known how to defuse situations with understanding, preventing violence from worsening, negotiating with governors to resolve problems one by one. But there was no real policy designed in favor of Black people. They were the ones, who through their courage, their determination and their non-violent strategy, with their numerous sit-ins and the famous "Freedom Riders", who did not hesitate to venture into the most racist towns of “Dixieland” where each time angry packs of the KU KLUX KLAN and local sheriffs conspicuously silent awaited them, when they did not send their dogs or water cannons to disperse the crowd before carrying out mass arrests; they were the ones who shook the foundations of segregation. They were finally going to be heard. That same day, President Kennedy delivered his magnificent “Civil Rights Address”.

“This is not a sectional issue. Difficulties over segregation and discrimination exist in every city, in every State of the Union. […] But law, alone, cannot make man see right. We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. […]

Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law. And this Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.”

A few hours later, Medgar Evers, a Black Civil Rights activist and World War II veteran, was murdered in front of his home in the presence of his wife and children, in Jackson, Mississippi.

1963 marked the hundredth anniversary of the abolition of slavery. A peaceful march “The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” was held in Washington in front of the Abraham Lincoln memorial on August 28, 1963. Bringing together nearly 300 000 people, a quarter of whom were White, it was the largest demonstration ever organized in the federal capital until then. A feeling of hope for all these activists and anonymous people, and a way of reminding Congress of the urgency to pass a strong bill for Civil Rights within the year. “We Shall Overcome”, a gospel song performed by Joan Baez, was followed by the unforgettable “I Have a Dream” by Martin Luther King, to which responded, two weeks later, the bombing of Birmingham in Alabama. Perpetrated on September 15, 1963, against a Baptist church, the attack killed four Black young girls and left a fifth one partially blind. The road to freedom promised to be long still.

In Vietnam, the situation was being monitored closely. Convinced, according to the famous domino theory, that if South Vietnam happened to fall into the hands of the communists then the rest of the countries of South-East Asia (Laos, Cambodia, Philippines, etc.) would follow the same path, The United States did not hesitate to put in place and support the dictatorial regime of the catholic Diem. A proven tyrant at the head of a corrupt and isolated regime, whose army was trained and financed by the CIA, he continually lashed out at Buddhists, excluded from political life and yet forming the majority in the South. Some bonzes even went as far as setting themselves on fire as a sign of protest. In June 1961, 600 “US military advisors” could be counted on site. In August 1963, while Diem organized the repression of bonzes throughout South Vietnam, no fewer than 16 000 American soldiers were now in the country.

From an ethical and moral point of view, the United States found itself in a difficult position. How far to go to contain the communists within their borders? While Kennedy had promised peace and prosperity to the rest of the world, the showcase presented by Diem was most embarrassing. On November 1, 1963, it was in any case a victorious coup d'état which got over this hated president, under the watchful eye of the Americans.

Just a few days later, on November 22, 1963, a shock wave crossed America. President Kennedy had just been assassinated in Dallas, Texas, in the middle of an official parade. A sniper's bullet hit his brain. He died at one in the afternoon. Probably the beginning of twilight and the turning point of the Sixties.

Lyndon B. Johnson as Vice President deputized and was elected 36th President of the United States in the elections of November 1964. Concerns remained unchanged; the Johnson administration still had its eyes fixed on Vietnam.

On August 2, 1964, we learned by the press that three PT boats (torpedo boats), identified by the American State Department as being North Vietnamese, attacked the USS Maddox, a destroyer which was operating in the Gulf of Tonkin, about 40 miles off the North Vietnamese coast. The reality is that this attack was a response to covert operations led by the United States against North Vietnam. Two days later, the press reported new naval battles in the same Gulf of Tonkin, citing unofficial sources. This information turned out to be inaccurate and just an excuse to show off some muscle.

America was going to succumb to the pressure of its right wing, listening ever more carefully to its military advisors. This resulted in the Gulf of Tonkin resolution of August 7, 1964, which gave President Johnson full powers. He was now able to use all the American military force he would deem necessary to defend American interests without prior control from Congress. This is how the United States gradually slipped into a most deadly spiral.

Johnson did not have the composure of Kennedy and at the beginning of 1965, he authorized Operation “Rolling Thunder”, a sustained bombing campaign against North Vietnam. “Then landed the first operational contingent, three thousand five hundred marines to protect the Da Nang air base, from where the B-52s, the gigantic strategic bombers built by Boeing, were taking off.[4]” The toll was heavy, 25 000 civilians killed within the year, the American army was not known for its intricate work. The Vietnamese jungle was beginning to smell strongly of napalm.

We were blowing up and burning down this country we were supposed to be saving.

(Neil Sheehan, former correspondent of UPI (United Press International), in episode 4: « The War in Vietnam (1961-1968) » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

On July 28, 1965, in a live television address from the White House, President Johnson announced the immediate sending of 50 000 additional troops, bringing the total American presence there to 125 000 men. To do this, he increased the number of the Draft Call (the call of young boys over 18 years old in a fit state to serve) from 17 000 to 35 000 men per month.

The Draft (or conscription) was implemented during World War II. At the age of 18, American boys were required to register in the draft lists for a possible mobilization. Depending on its needs, the army called on these young men who became the Drafted (the enlisted). With this irony, that they were considered too young to be able to vote but not to go to war. Exemptions existed, particularly for those continuing a college education, thereby favoring children from the well-off. Thus, many children of parliamentarians did not go, which kept fueling a feeling of injustice.

As for the others, they hence only had their eyes left to cry or the difficult option of going underground. Little by little, the Draft Resistance was organizing. Like David J. Miller, this 22-year-old pacifist, who on October 15, 1965, did not hesitate to publicly burn his Draft Card (his order of enlistment) during a demonstration in New York, thereby risking a $10 000 fine and a sentence of up to five years in prison. Thousands of young people would follow his heels, before ending up, for some, getting lost in the wandering of artificial paradises.

Like Kerouac's heroes in the book On the Road, an emblematic work of the Beat Generation published in 1957, thousands of young people were about to start their initiatory journey to the West, heading towards the Promised Land, San Francisco, “the craziest city in America”. There the Beautiful People awaited them, who, by way of LSD, were promising fraternity, love and peace. In search of a new horizon and eager to find some spiritual meaning in life, far from the materialist paradigm offered by American society, these uprooted kids would for a time succumb to the call of the Other World thanks to the wonders of chemistry.

Discovered in Switzerland in 1938 by Albert Hofmann, a researcher at Laboratoires Sandoz, working on the development of analgesics, the hallucinogenic effects of LSD were immediately identified. The Nazis took advantage of the opportunity to conduct multiple experiments with the aim of eliminating the will of the subjects treated with the ambition of being able to exercise total control over the brains of their enemies. The CIA, which thereafter laid hands on these reports, got the green light from Dulles to deal with this research in depth. Large doses of acid were first imported from Switzerland, before being gradually replaced by a domestic production. In order to carry out this research, numerous scientific foundations were about to see the light of day, not hesitating to set foot on American campuses.

LSD was not yet an illegal substance and the researchers had no trouble recruiting a cohort of volunteers, paid $20 per session, who came to enjoy a “trip” at the CIA’s expense. Among them, Ken Kesey, the author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1962). With his band of Merry Pranksters, he became the champion of acid consumption and one of the main architects of the propagation of psychedelia.

He thus organized the Acid Tests, these giant parties, where the acid was diluted in large pitchers of Kool-Aid, a sort of punch, and where rock music, beating to the sound of the Grateful Dead, dance and the strobes light, were enabling the crowd to access the Holy Grail. The idea was to be in tune with the Universe, free humanity from its bad vibrations by taking LSD and, in this collective effort, purge the world of its hatred and ugliness; a utopia that spit out thousands of junkies.

Already in 1956, Allen Ginsberg warned in the poem Howl:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,

starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for

an angry fix…

These young people in great distress could be found in the famous Haight-Ashbury district and the only ones to show some concern and come to their aid were the Diggers, an avant-garde theatrical troupe.

Each day, they collected huge sides of beef from nearby butchers and cooked a stew which they distributed for free. They also organized clothing collections which they stored in a warehouse where everyone could come and find something to wear. They were finally an attentive ear for this desolate and suffering community. They did not hesitate to regularly publish press releases that they displayed in town, some of which send shivers down your spine:

Pretty little 16-year-old middle class chick comes to the Haight to see what it's all about & gets picked up by a 17-year-old street dealer who spends all day shooting her full of speed again & again, then feeds her 3000 mikes and raffles off her temporarily unemployed body for the biggest Haight Street gang bang since the night before last. The politics & ethics of ecstasy. Rape is as common as bullshit on Haight Street. […] Kids are starving on the Street. Minds & bodies are being maimed as we watch, a scale model of Vietnam. […] Are you aware that Haight Street is just as bad as the squares say it is?

Chester Anderson

April 16, 1967

From dream to nightmare, 1967 marked the lost illusions of the Beautiful People. Haight-Ashbury had become a zoo where tourist buses followed one another filled with squares (middle-class persons) coming to witness the show of these young people on the road to perdition and where fraternity went out the window in a dog’s age. Them who were fleeing the rigidity of their homes and a sanitized world were now caught up by the leisure society, becoming despite themselves consumer goods. The loop was closed.

In 1966, California and Nevada became the first states to ban the production, sale and use of LSD. In 1968, a US federal law made its possession illegal throughout the United States. The end of recess had chimed. And yet, as a final nose-thumbing to the authorities, the summer of 1967 was dictated Summer of Love.

After the incredible Monterey Pop Festival on June 16, 17 and 18, which saw bloom Janis Joplin and Otis Redding become known, hundreds of thousands of young people would gather in the largest cities of America, from the Golden Gate Park in San Francisco to Los Angeles by way of New York, Detroit or Miami, to celebrate love in music and on acid.

Peace, Love & Rock’n Roll, and the group that was acing in 1968, were indeed the Doors. Since the success of the title Light my Fire, released as a single in April 1967 and which reached the 1st place on the Billboard 100 in July 1967, the group was experiencing a lightning ascent. It seemed a long time ago when Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek, both newly graduates from UCLA (University of California Los Angeles), met on Venice Beach one afternoon in July 1965, and decided to form, with this energy and enthusiasm of youth, what would become one of the greatest rock bands of all time, selling on their own more than 100 million albums around the world. That same summer, they would be joined by guitarist Robbie Krieger and drummer John Densmore. The legend could begin.

In May 1966, they landed a contract at Whiskey A Go Go, a trendy bar on the famous Sunset Strip, where all the youth of Los Angeles flocked to. They were for instance the opening act for Them, a band came straight from Belfast, and led by the sulfurous Van Morrison. The Doors were thus learning from the best. If the beginnings were quite timid, Jim Morrison having difficulty establishing himself in front of the public, he quickly found his footing and little by little his acting style was put in place. So when he launched into the verses of his song The End and added, probably under the influence of LSD, a:

Father? Yes, son? I want to kill you

Mother? I want to fuck you all night long

The group was squarely kicked off the bar. What does it matter? In November 1966, they signed a contract with Elektra Records, for a commitment to seven albums.

WHISKY A GO GO ON SUNSET STRIP, 1966.

On January 4, 1967, they released their first album, simply titled The Doors. It included in particular the songs Break on Through, Light My Fire and The End with the oedipal lyrics added to the recording. It remained in the top 10 of the American charts for almost ten months. Barely a few months later, on September 25, 1967, they kept it going with the release of their second opus, Strange Days. Despite being in the shadow of the first album which was still well ahead of sales, there was no lack of commercial success.

At the end of summer 1967, photographer Joel Brodsky immortalized Jim Morrison posing shirtless with his famous leather pants, in a series of black and white photos, entitled “The Young Lion”. Now set up as a sex symbol, the Doors frontman made the cover of magazines. In just a few weeks, he rose to icon status, idolized by thousands of fans. Finding it ever more difficult to cope with the pressure of fame, he then drastically increased his consumption of drugs and alcohol.

In December 1967, it was squarely on stage, in the middle of a concert, in New Haven, Connecticut, that he got arrested by the police for indecent conduct. A first in the world of rock music, which contributed to forge his image as a rebel and added to the mysticism that was surrounding him.

Right in the middle of his performance, Jim Morrison suddenly stopped, lighted a cigarette and began to tell a stunned audience about an incident that had just taken place a few hours earlier backstage. While he was in the shower area with a girl, a police officer surprised them and, not recognizing the leader of the Doors, asked them to leave. To which the singer would have replied: “Eat it!”. The policeman then took out a tear gas canister before warning: “Last chance!” and Jim Morrison answered back: “Last chance to eat it!” and ended up being sprayed with irritating gas. Obviously, during his story, Morrison took the opportunity to openly mock the police officer in question, going as far as to call him a “little blue pig”. The police officers ensuring safety on site most probably did not have the same sense of humor.

When in January 1968, the Doors went into the recording studio to produce their third album Waiting For The Sun, the atmosphere was far from being set fair. Joan Didion, who, one spring evening, dropped by Sunset Sound Studios, reported on that palpable tension.

Jim Morrison was missing. For some time now, he got into the annoying habit of coming late, most often in a state of intoxication when he was not completely stoned. The wait was becoming increasingly oppressive for the other members of the group. But there you go; Jim Morrison was demotivated and lacking inspiration. The recording of the disc took almost five months after a most laborious process. Joan Didion herself “did not see it through”.

On July 3, 1968, Waiting For The Sun was finally released. It would be the only Doors album to reach No. 1 for four consecutive weeks. The title Hello I Love You which opens the album also took the lead on the Billboard and became the group's best seller since the success of Light My Fire. And for the first time, the Doors entered the English charts, climbing directly to 16th place.

On July 5, 1968, they followed up with a legendary concert at the Hollywood Bowl, the only one to have been filmed in its entirety. For the opening act, they got none other than the Chambers Brothers and Steppenwolf. Jim Morrison was in good shape and gave a quality performance. Everything seemed to be going well. So there was a general amazement when he announced to the other members of the band his intention to stop playing music to dedicate himself exclusively to poetry and film production.

This year of 1968, definitely was placed under ill omens.

If you look at the whole year as theater, as real acts of tragedy, there’s an almost poetic feeling to it. 1968 was one goddamn thing after another.

(Lance Morrow, essayist at Time Magazine, in episode 8: « 1968 » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

On the night of January 30 to 31, 1968, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NFL), otherwise called the Viet Cong, taking advantage of the Tet festivities which mark the transition to the New Year, launched a general offensive throughout South Vietnam. Some 80 000 communist soldiers simultaneously assaulted the country's largest cities, including Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam. Key buildings were targeted, among which the brand new American embassy, yet considered impregnable. The astonishment was absolute. Americans and South Vietnamese were taken completely by surprise, thereby exposing the weak control of the American army.

The imperial city of Hue, historic capital of Annam, was not regained until March 2, at the cost of fierce fighting. It numbers among the bloodiest battles of the Vietnam War, with several thousand civilians executed, lying in the middle of a city in ruins.

If the Viet Cong ended up suffering a military failure, with half of its men out of action, including more than 30 000 killed and thousands taken prisoners, the political success, as for it, was unequivocal. Indeed, the psychological impact of the offensive on American public opinion eventually got the better of the Johnson administration.

The United States counted more than 20 000 dead in Vietnam at the end of 1967, some 500 000 soldiers deployed and billions in military expenditures, the pill was therefore extremely bitter. Certain unease began to spread among the American population. Either the government had lied about the conflict proceedings, pointedly repeating “we are winning in Vietnam”, or it had no idea what was really happening there. And Walter Conkrite, star of CBS News, to sum up the general feeling:

It seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam, is to end in a stalemate.

(Episode 4: « The War in Vietnam (1961-1968) » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

On this February 27, 1968, with these few words, President Johnson was about to lose the support of Middle America.

1968 was an election year and opponents to the war were looking for a new leader. Like many others, Robert Kennedy was approached but refused the offer. Among the close relations of the Kennedy clan, it was considered that the nomination of the Democratic Party was in the hands of the President. LBJ seemed unbeatable; Bobby's turn would come in 1972. Indeed, running against the incumbent President of your own party remained a taboo.

Ultimately, the role fell to Eugene McCarthy, Senator from Minnesota. Coming from the left wing of the party, he was not considered at that time a serious potential candidate. Johnson did not sense danger. Yet, with his platform “Peace”, McCarthy became a sounding board for a large part of the youth overcome by frustration and even despair faced with the situation in Vietnam. Many students would join him, and also for the requirements of the campaign and the traditional door-to-door, cut their hair and shave their beard, with the famous slogan “Get clean for Gene”.

On March 12, 1968, the first primary of the Democratic Party unfolded in New Hampshire. If McCarthy reached even 30%, then he could legitimately claim a major victory. He obtained 42% of the votes.

It was a hard blow for Johnson who did not even campaign so much his nomination to run for a second term seemed obvious to him. But, combining all the votes, he was below the 50% mark. Such a humiliation facing a candidate almost unknown to everyone not long ago, spoke volumes about the President's vulnerability. Within the Democratic Party, everyone took cognizance of the result and repositioned himself. Thus, on March 16, 1968, Robert Kennedy, in turn, announced his candidacy for the Presidential election of the United States.

In view of this new political reality, and in a context of general discontent with the Vietnam War, where not a day went by without a demonstration taking place in the country, President Johnson ended up throwing in the towel. In a television address on March 31, 1968, he announced not “wanting” to run for office. It was a political earthquake.

He who rushed Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act in 1964, and signed the Voting Rights Act the following year, while initiating the implementation of numerous social programs such as Medicare, thus remained forever tied to the fate of this war, judged responsible for having sent thousands of Americans to be decimated on the other side of the world. Already in 1965, Johnson made this terrible admission:

… a man can fight if he can see daylight down the road somewhere, but they ain’t no daylight in Vietnam. There’s not a bit.

(Phone conversation on March 6, 1965, with Richard Russell, Senator of Georgia. Episode 4: « The War in Vietnam (1961-1968) » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

He had just paid a high price for it that day.

It was in the same month of March that Joan Didion went to Alameda prison in California to visit Huey P. Newton. It could have been the banal story of a young Black man arrested in the United States, except that Newton was one of the founders of the Black Panther Party.

HUEY P. NEWTON, ALAMEDA COUNTY JAIL, CALIFORNIA, 1968.

I suppose I went because I was interested in the alchemy of issues, for an issue, is what Huey Newton had by then become. […] In many ways he was more useful to the revolution behind bars than on the street.

On October 28, 1967, around 5 a.m., while Newton was at the wheel of his car with a friend, John Frey, an Oakland police officer, carried out checks on it. Recognizing the leader of the Black Panthers, Frey called for reinforcements. What happened next is chaotic and uncertain. Newton was arrested and from there shots would have been fired on both sides. Officer John Frey was shot four times and died within the hour. He was 23 years old. His colleague Herbert Heanes was in critical condition, he was shot three times. As for Huey Newton, he was taken to Kaiser Hospital in Oakland to treat a bullet to the stomach. He was incarcerated immediately after. He faced the death penalty at just 25 years old.

At this time, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense was still in its infancy. Created a year earlier, on October 1966, by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, two former students of Merritt College in Oakland, their ideological line was inspired by the most emblematic or radical figures of the time, especially Che Guevara and Malcolm X.

From one they took over the military symbolic and from the other the criticism of the choice of non-violence made by the main leaders of the fight for Civil Rights. A few months before his assassination, on February 21, 1965, Malcolm X, however, performed a turnaround by calling to support any movement in favor of Black people, thereby promoting the fact of going beyond Black Nationalism and opening the possibility of alliances with leaders of movements led by Whites, which proved to be very useful when defending Newton.

The Black Panthers then advocated direct action and above all claimed the legitimacy of armed self-defense, always within the strict framework of the law. Newton believed that Black people were discriminated against in part because they were ignorant of the laws and social institutions that could protect them, namely, for instance, the permit of the unconcealed carrying of weapons, in accordance with the Second Amendment of the United States Constitution and the legislation still applicable at the time in the State of California.

This idea that violence could be considered as the essential vector for any social change had slowly gained ground among a growing portion of the younger generation. Black people were tired of mourning their dead and, for some time now, the pacifist doctrine of Martin Luther King, considered ineffective or even dangerous, had been eclipsed in aid of a more radical activism.

This new direction was also in line with Black Power, a concept defined by Stokely Carmichael, elected in 1966 at the head of the SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), one of the historic organizations of the Black movement. After his mandate, the SNCC would only keep non-violence in the name, Carmichael exhorting to the political autonomy of Black people and the necessity of the quest for power, the only condition according to him to their emancipation.

Present during the Selma March in 1965, alongside Martin Luther King, a journalist questioned him about the use of violence. Here is what he said:

Well I just don’t see it as a way of life. I never have. But I also realize that no one in this country is asking the White community in the South to be nonviolent. And that, in a sense, it’s giving them a free license to go ahead and shoot us as will.

(Episode 5: « A Long March to Freedom (1960-1968) » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

In Oakland, relations between the police and inhabitants of Black neighborhoods had deteriorated for a long time. Between harassment and unjustified daily beatings-up, the population suffered the wrath of an endemic and institutional racism, less spectacular than in the South but just as devastating.

The Black Panthers therefore decided to traverse the city by car in order to oversee the smooth running of the various questionings or arrests, like a vigilanti patrol, ready to intervene in the event of any police misconduct. Always at a good distance but clearly visible, weapons in hand, they aimed to be a deterrent force. An affront to the authorities, who without delay whipped out the Mulford law, adopted in July 1967, prohibiting the carrying of loaded weapons in public spaces in the State of California.

In fact, forced to abandon armed patrols, the Black Panthers reoriented their action with the implementation of multiple social programs which found a positive response among the population.

For instance, they founded the Oakland Community School, a free school providing quality education to nearly 150 children from poor neighborhoods. They opened free dispensaries, to facilitate access to healthcare for the Black community, or even distributed breakfasts, also free, for the poorest children. More than 20 000 breakfasts would be served each week in 19 cities across the country, solidarity being their operative word.

A left-wing party, the Black Panthers saw themselves from the start as an anti-capitalist and internationalist movement. So for them, the fight for the emancipation of Black people was not part of a racial struggle but rather a class struggle. It would also be one of the first Black organizations in the country to claim to adhere to communism. It was enough to be in the crosshairs of a certain Edgar Hoover, who more than anything, feared the arrival of a new “Messiah”, and would not hesitate to describe this distribution of breakfasts as danger to the nation.

From then on, everything would be done to discredit the movement. Infiltrations, disinformation, mass arrests, or disguised assassinations, the dark hours of COINTELPRO (counterespionage program) were about to chime.

And yet, one just have to linger for a moment over the 10-point program drawn up by Newton and Seale, a sort of party manifesto, to realize that there was nothing very revolutionary about it. It by the way refers to the American Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Better access to housing, employment, education, the stop of lynchings and police brutality, fair justice, demands that seem to be self-evident today. Because if in the South they fought for Civil Rights, in the North they demonstrated above all for the right to work and to dignity. A profound anger was simmering in the ghettos of which the Watts district still bore the scars.

Like many others, Newton was one of the children of the 2nd Great African-American Migration settled around the San Francisco Bay Area. With his Executive Order 8802, signed on June 25, 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt prohibited racial discrimination in the defense industry. A pull factor and an opportunity that more than 5 million Black Americans would seize, ready to give up everything in the hope of a better life. Destination the Northeast, the Midwest, but also the West Coast of the United States, to cities like Oakland, Phoenix, Portland or Seattle, which then benefited from numerous jobs in the military industry.

However, the welcoming committee was not the warmest, as evidenced by the discriminatory practice of “redlining”, consisting of preventing certain minorities, including African-Americans, from renting or buying houses in certain neighborhoods. Thus, in Los Angeles, most of the city was tacitly forbidden to them. Two of the few neighborhoods where Black people could settle were Compton and Watts. A segregation that did not have the name but that showed all its forms. And to this would be added a myriad of injustices.

For similar housing, rents remained much higher for Black people than for White ones, with buildings for the most part unsanitary and damaged. Regarding education, the lack of resources was also sorely felt. Two-thirds of the Watts neighborhood's residents did not complete high school and an eighth was illiterate, while at the same time, employment discrimination still applied outside the defense industry. Market prices also remained higher for Black people, with businesses run by Whites having a habit of underpaying Black employees while maintaining very high sales prices, making many goods de facto inaccessible. And if we finally tally the incessant police brutality – between 1963 and 1965, 65 residents of the neighborhood were killed by the police, including 27 in the back and 25 unarmed – we have here all the ingredients of a social powder keg.

On the evening of August 11, 1965, Marquette Frye, a young Black man of 21 years old, was arrested while driving his mother's car. He tested positive for alcohol after submitting to a Breathalyzer. The police officer in charge, Lee Minikus, therefore arrested him for drunk driving and called a reinforcement team to seize the vehicle. It was then that Marquette's brother, Ronald Frye, also present, left to look for their mother, Rena Price, who arrived a few minutes later at the scene of the incident. The voice raised in front of an increasingly large flock of passersby and police officers. Between melees, shouts and blows, the police officers were quickly overwhelmed so much so that they tried to pick up Ronald Frye by force. Witnesses to the scene then warned other residents of the neighborhood. Furthermore, a police officer would have hit a pregnant woman; they now came running en masse.

The result: six days of riots, where from August 11 to 17, 1965, the entire neighborhood was transformed into an absolute battlefield. Police Chief William H. Parker did not hesitate to involve the army and establish a curfew zone of 39 mi². Ultimately, more than 15 000 men of forces of law and order were mobilized. The death toll stood at 34, some 1000 injured and nearly 3500 arrests. The ghettos went up in flames, with many buildings and vehicles being set on fire to cries of “Burn Baby Burn”. Three years later, we would hear these same words resonate at the death of Martin Luther King. This time the insurrection would affect the entire country.

For the moment, the Black Panthers' concern was to do everything to transform Huey Newton into a political prisoner. The whole issue for the party was to succeed in establishing itself as a legitimate protest voice and in the long term becoming part of the Californian radical left-wing movement.

The task promised to be difficult. At the time Newton was arrested, the party counted barely more than the few members who formed its organizational chart. Namely, the President Bobby Seale, the Defense Minister Huey P. Newton, the spokesperson and Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver, or else the Communications Secretary Kathleen Cleaver.

This former SNCC recruit, she held the position of secretary in the New York division, knew perfectly the inner workings and organizational mechanics of a large-scale movement. She, who joined the Black Panthers in 1967 and married Eldridge Cleaver in December of the same year, was therefore going to be in charge of the campaign for the release of Huey Newton. Alliances would prove to be more than necessary, on the one hand to broaden the party base and on the other hand, to have at their disposal an operational structure capable of orchestrating the campaign.

A first rapprochement was carried out with the brand new Californian Peace and Freedom Party. This predominantly White political party campaigned in particular for women's rights, firmly fought against the war in Vietnam, and wished for greater support from the government to the Civil Rights movement, whose policy and measures taken were judged to be too slow and not quite effective.

In January 1968, more than 100 000 activists joined the party, thus qualifying Peace and Freedom for the November 1968 election. An alliance with the Black Panthers meant privileged access to the Black vote in the San Francisco Bay area. As for the Black Panthers, this allowed them to spread their message beyond the Black community, making Huey Newton the martyr-hero of the entire radical left. Newton was going to be tried by a mostly White jury, facing a White judge and White lawyers, so it was essential to emphasize the racial character of the trial, while relying on a large base of supporters, what is more, White and very active.

The masterstroke was not long in coming. On the occasion of Huey Newton's birthday, on February 17, 1968, two galas were organized, one in Oakland, and another one the next day in Los Angeles, under the joint aegis of the Black Panthers and the Peace and Freedom Party. Bringing together nearly 5000 demonstrators in support of Huey Newton, the slogan “Free Huey!” became the rallying cry of the protest; it would now be printed on buttons and t-shirts.

The event was also marked by the announcement of a partnership with the SNCC, the opportunity for Stockely Carmichael to take the floor. The catch was significant, Carmichael being considered one of the most famous Black activists in the world. SNCC executives were also appointed to key positions in the organization. Stockely Carmichael thus occupied the position of Honorary Prime Minister and H. Rap Brown the one of Minister of Justice. However, the union only lasted for a short period of time before disintegrating a few months later, coming up against the intransigence of Black Nationalism advocated by the SNCC, which therefore took a very dim view of the alliance with the mostly White Peace and Freedom Party. But in this mid-February, the publicity coup was definitely real. So the Black Panthers were not going to stop there.

Every day, protests took place outside the Alameda courthouse, making the courthouse the focal point of activists, sympathizers, police and the media. The latter would have a field day with them. The Black Panthers were attractive. With their afro cut, their beret, their sunglasses, and their black leather jacket, they had a look that stood out and cut a fine figure. Everyone fought over them; the written press and television, papers about them were what sold.

The party would also ensure the regular presence of a certain number of its members and sympathizers in the public gallery of the courtroom. The objective being on the one hand, to show Newton that the Black Panthers were not abandoning him, to maintain constant pressure on the jury, and on the other hand, to suggest to the Whites that the movement was much more powerful than they could imagine, the people present in the courtroom forming theoretically only the tip of the iceberg. The revolution was underway.

This strategy was not without consequences for the party members. As the protests grew, police repression against the Black Panthers intensified. In the eyes of the FBI, the campaign to free Huey Newton did only confirm the need to neutralize the organization. Thus, Bobby Seale was arrested at his home, accused of conspiracy to commit murder.

The Cleavers, who lived in an apartment on Oak Street, were constantly being watched by the FBI. Suspected of hiding weapons, police searches were regularly carried out at their home. The excitement was therefore palpable when Joan Didion paid them a visit at the end of February. That same day, Eldridge Cleaver published Soul On Ice. In the book, he revisited his criminal past and recounted his experience at the Folsom prison, in California.

Arrested at the age of 18 for marijuana trafficking, he was convicted again in 1958, this time for rape, assault and attempted murder. The passage where he explained how he saw rape as an act of political inspiration caused a stir. For that matter he admitted having initially attacked Black women in the ghetto, in order to “practice”, before continuing and embarking on a series of White women rapes. Prison having transformed him, he said he unequivocally renounced the practice of rape and its insurrectional justification.

The success of the book was in any case immediate. Hundreds of thousands of copies were sold, fast-tracking Eldridge Cleaver, and even more so the Black Panthers, into the international foreground. Against all expectations, Eldridge Cleaver even became the moral backing of the intellectual left. Released in 1966 on parole, Cleaver's supervision was not supposed to end until 1971. The Sixties were magnificent in that everyone seemed to believe they could reinvent themselves. The presence at the Cleavers of the parole officer at the time of Joan Didion's visit demonstrated that this was not entirely the case.

KATHLEEN AND ELDRIDGE CLEAVER, ALGER 1969.

Huey Newton had become the symbol of the African-American struggle against White power. Proof of this sudden notoriety, the interviews came one after another for the co-founder of the Black Panthers. So Joan Didion was not the only one to show an interest in him. During their interview, a radio presenter and a journalist from the Los Angeles Times were also present. Eldridge Cleaver himself was there.

Political hero dictates, everyone wished for a piece of “God’s word”. Statements were needed to satisfy the press and activists. Thus we could hear Huey Newton quoting James Baldwin: “To be Black in America is to live in a constant state of rage.” No one could then imagine that a few weeks later, Martin Luther King would be assassinated, shot in the throat, while he was getting some fresh air on the balcony of his motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Once again, the heinous act of a segregationist.

The response came without delay. Riots broke out in more than a hundred American cities: Washington, Chicago, Detroit, Boston, New York, to name a few. Unable to contain their anger and indignation, Black people’s grief was being expressed through violent destruction. Once again the ghettos went up in flames. In Washington, the tension was such that machine guns were placed on the steps of the Capitol. At the end of three weeks of unrest, nearly 20 000 arrests could already be tallied.

On Martin Luther King’s tomb is engraved this epitaph extracted from an old Negro-spiritual, the sacred music of Black slaves:

Free at last, Free at last

Thank God Almighty, I’m free at last

He had sung these same words at the end of his incredible “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963. Unfortunately, on this April 4, 1968, death still seemed the only possible liberation for Black people in America.

In retaliation, Eldridge Cleaver decided to lash out at police. According to him, to remain at the vanguard, the Black Panthers had to react firmly. He therefore spoke about his project to members of the Oakland party. The older ones all refused altogether, for them it was suicide. But the youngest did not have the same opinion. Thus, on April 6, 1968, Eldridge Cleaver and 14 other Black Panthers ambushed a patrol of Oakland police officers. Among them was Bobby Hutton, the party’s treasurer. The Black Panthers were armed with hunting rifles and M-16s, these assault rifles used by the American army. The police, who came under fire, then cornered the Black Panthers into a house. Entrenched in the cellar, it caught fire following a shot of tear gas grenade. So to avoid burning alive, the Black Panthers chose to surrender. Bobby Hutton went out first with his hands in the air. He was shot dead on the spot. He was only 17 years old. Cleaver did advise him to undress completely, but modest, Hutton kept his pants on. During the confrontation, two police officers were hit and Cleaver himself was injured. After this fiasco, and in order to avoid prison, Eldridge Cleaver fled to Cuba, before ending up going into exile in Algeria in 1969.

The war did not care about what was happening in the country and continued to rage. 1968 was the deadliest year on the American side, with the loss of nearly 17 000 men. That was almost as many as the dead recorded from the start of the conflict until the end of 1967, which goes to show the intensity of the battles that took place every day.

From their sofas, the Americans watched stunned the body bags of soldiers piling up. Massive bombings had long extended to Laos, then to Cambodia, supposed rear bases of the Viet Cong. On television, “testimonies multiplied about South Vietnamese prison conditions, the torture that the prisoners were subjected to in the presence of American advisors, some of whom participated directly in the sessions. Stories of civilian killings in villages were added to the images of daily bombings that Hanoi was suffering.[5]”

The left-wing student organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), formed in the early 1960s in the context of the nuclear arms race, had become one of the main voices of opposition to the Vietnam War in the student sphere. Its concerns were varied and covered topics ranging from economic and social justice to the fight for Civil Rights, from the dismantling of private monopolies to the promotion of participatory democracy.

Present on more than 50 campuses across the country and proud of some 100 000 members, it first organized the “10 Days of Resistance”. Sit-ins, “teach-ins” (small conferences on current issues), rallies and protest marches came one after another in American universities. On April 26, nearly a million students went on strike throughout the country. It was unprecedented.

On the campus of Columbia, events took a more militant turn. On April 23, students barricaded themselves inside university buildings, even going as far as taking hostage for 24 hours, the university dean, Henry S. Coleman. What were their grievances? On the one hand, the university collaboration with the IDA (the Institute for Defense Analyses), a think tank with close ties to the Pentagon, and whose research was dedicated to war armaments. And on the other hand, the building project of a gymnasium between Harlem and Morningside Heights, likely to induce de facto an unwanted segregation in the community.

On April 30, after eight days of occupation, the students were forcibly evicted after the intervention of the New York Police Department, the NYPD. That said, the university later agreed to dissociate itself from the IDA and abandoned its gymnasium project, proving to students that their actions could lead to change. Columbia then became the symbol of the student revolt.

Civil society was not outdone. On April 27, hundreds of thousands of people marched in 17 cities across the country to protest the Vietnam War and in some cases racism. In New York, more than 100 000 demonstrators thus met at Sheep Meadow in Central Park.

At Berkeley, students didn't even hide anymore. A ceremony, called “Vietnam Commencement,” was held on campus on May 27, in which students and faculty members signed an oath refusing to participate in the war and then openly proclaimed before the assembly:

Our war in Vietnam is unjust and immoral. As long as the United States is involved in this war I will not serve in the armed forces.

(Archives from University of California, Berkeley. Cf. footnotes).

There were some 900 signatories. Ronald Reagan, then governor of California, described this ceremony as indecent, bordering on obscenity. Although legal, this gathering was more than contemptible for him. The irony being that he argued that the only reason these demonstrators were not guilty of treason was the lack of an official declaration of war by the United States against North Vietnam.

The climate was such that it now became obvious to all the political leaders competing in the presidential election that this war had to be put an end to. The whole question remained to know how. In the meantime, the electoral campaign would resume its rights.

Robert Kennedy won the primaries in Indiana and Nebraska in turns, before suffering a clear setback in Oregon against McCarthy on May 28. To maintain his chances and obtain his ticket for the Democratic convention in August in Chicago, he absolutely had to win the California primary. After many scares it was taken care of on June 4 and with a large victory of 46%. The Kennedy clan could smile again and thousands of young people with it. Bobby Kennedy still remained for many the only credible hope to a real political change. After his victory speech on the morning of June 5, at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, and while he was preparing to celebrate the result of the primary, he was shot several times in a corridor of the hotel, located behind the kitchens. He died the next day at 1:44 a.m., at Good Samaritan Hospital, at the age of 42.

This time that was it. Even Elvis wrote his own protest song with the title If I Can Dream, recorded in the NBC studios in June 1968 for his Christmas Special Comeback. And a question that tormented America: What was it becoming?

Unfortunately the country had more surprises to come. The month of August arrived and the time for presidential nominations. Hoping to obtain nothing from the Republicans, the SDS students, soon joined by the Mobe (the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam) and the Yippies of the Youth International Party, decided to go to Chicago to get themselves heard and put pressure on the Democrats at the party's national convention scheduled for August 26-29. The idea: to tip the scale in favor of an openly anti-war candidate.

All requests for having permission to demonstrate were refused by the mayor of Chicago, Richard J. Daley, one of the bosses of the Democratic Party. And yet, he knew full well that thousands of young people would still make the trip. On Sunday, August 25, the day before the official start of the convention, around 10 000 people thus found themselves wanting to camp at Lincoln Park. If the atmosphere was initially festive, between dance, music and improvised yoga sessions, helped by the somewhat sassy Yippies, who mixing happenings and politics, didn’t hesitate to show up with their own candidate, a 200 pounds pig named Pigasus, tension would quickly rise in the vicinity of the park.

Daley, wanting to enforce "law and order" in Chicago, words that he could have extracted from the mouth of Nixon, freshly invested by his party during the Republican convention, on August 5 in Miami, Florida, had just put his city in a virtual state of siege. For this, he called on, no more, no less, 12 000 police officers, 5600 men of the Illinois National Guard and 5000 soldiers who came straight from the Fort Hood military base in Texas. The International Amphitheater where the convention was to be held, looked like an authentic fortress surrounded by barbed wire. A curfew at 11 p.m. in all the parks of the city had also been established, forcing demonstrators to evacuate the premises. Every evening, they were driven out a little more violently by way of baton blows and tear gas.

Soon these scenes of violence would reflect the atmosphere inside the convention hall. The Democratic Party was in crisis. Lacking uncontested leadership after Johnson's withdrawal and shaken by the death of Robert Kennedy, the convention would lay bare for all to see the untenable divisions which pitted against delegates whose political currents were poles apart, between liberals from the North and conservatives from the South. Since the union could only be achieved on a ridge line, the debates around the Vietnam War and the choice of the next Democrat candidate would finish firing people up.

George McGovern, Senator of South Dakota, had entered the running. On the side of the opponents to the war, there was a free space and Robert Kennedy had many delegates who would now be divided between McGovern and McCarthy. Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey was also running for office. Supported by Johnson, he could rely on the backing of the party moguls who controlled enough delegates to override the primary process and the authority of the ballot, which obviously didn’t fail to irritate some people.

Invectives, shouts and jostles punctuated the debates. Connecticut Senator Abraham A. Ribicoff even went as far as declaring that with McGovern as President, they would not have had to deal with Gestapo-like tactics on the streets of Chicago. Mayor Richard J. Daley raised his fist; insults could now be heard flying from all sides. Dan Rather, a well-known journalist covering the convention for CBS, was violently grabbed by security agents while attempting to interview delegates. It was an appalling spectacle.

Outside, demonstrators had gathered in front of Grant Park, next to the Conrad Hilton Hotel where most of the delegates, including Humphrey and McCarthy, were staying, when the unthinkable happened. For almost twenty minutes, the police, literally raging, began to rain down blows, without any restraint, upon everyone present on site. People were screaming. Some, bloodied, were dragged by their feet to the police vans in total chaos.

There were pools of blood on Michigan Avenue.

(Gloria Steinem, journalist, in episode 8: « 1968 » from the documentary series about the Sixties. Cf. footnotes).

Americans watched this lynching live from their television sets, an absolute scene of carnage. The angry crowd chanted: “The whole world’s watching!” Later that night, it was finally Vice President Humphrey who was nominated as the party's candidate. The smiles were just a facade; any illusion of unity within the political family had just been left in tatters. The Democrats no longer seemed to be able to appease the nation. The contrast with the Republican convention, which took place in a most convivial atmosphere, marked by a certain enthusiasm, was scathing.

On November 5, 1968, the Americans apparently chose a return to order. Richard Nixon won the presidential election and was elected 37th President of the United States. We can still acknowledge the performance of Humphrey who only lost by a difference of less than 50 000 votes, in what remains one of the closest elections in American history.

When by a morning of November, Joan Didion went to San Francisco State College, she didn’t know yet that she would grapple with the longest student strike on an American campus in the history of the country. She, who missed Berkeley and Columbia, had promised to attend the current revolution in San Francisco. She simply emerged from it disappointed, taken aback by the scenes of "disorder" whose protagonists each seemed to play a role in what looked much like "a musical" rather than a serious and thoughtful approach.

It all began on November 1, 1968 with the suspension of George Mason Murray, a graduate student in the English Department who also happened to be Minister of Education of the Black Panther Party. Hired part-time as a professor in that same department, he was responsible for teaching introductory English courses for minority students accepted to the university under a special program. Following remarks deemed as incendiary that he would have made, the board of directors of the establishment was going to force his sidelining.

Thus, during a meeting at Fresno State College (California), he would have supposedly declared: "We are slaves, and the only way to become free is to kill all the slave masters." At San Francisco State College, he would have advised this time Black students to bring firearms to the campus in order to protect themselves against the White and racist administrators.

The incident would be the triggering factor for multiple confrontations within the very grounds of the university. The suspension of Murray being considered as racist and authoritarian, it reflected according to the students the proper downward slide of American society. On November 6, they hence started a strike that would last almost five months. At the maneuver, the Black students of the Black Student Union, the members of the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of the various organizations representing each minority, and the sympathizers mostly white of the SDS (Students for A Democratic Society).

Facing them, the president of the university, S.I. Hayakawa, was intractable. As agreed with the board of directors and the governor of California, Ronald Reagan, he authorized multiple police raids within the campus itself in order to restore order. Billy clubs in hand, hundreds of students were arrested, not without first getting hurt.

The students’ main demands revolved around racial inclusion. Black students wished for more visibility, both in terms of the number of admitted students from different minorities than on the one of teachers of color recruited. They also wanted for the academic program itself to be in tune with their current issues and concerns and thus be able to offer an answer to the question of their place in American society. They were eager to learn about their history and culture in order to acquire the tools they could pass on in return to their respective communities.

If the atmosphere seemed festive to say the least, an appropriate optimism winning over the troops, only Black activists could be considered “serious” according to Joan Didion. Very critical towards the White SDS students, she then observed with amusement the talking points of these young bourgeois who suddenly took themselves for guerilleros. Indeed, during the 1960’s, about fifty countries achieved independence.[6] A wind of freedom was blowing across the world and the word “revolution” was slipping out of everyone’s lips.

And she was then far from being the only one to think that the SDS activists were ultimately made up of merely young, privileged White people from wealthy suburbs whose parents, perhaps despite themselves, continued to make difficult the liberation and fulfillment of the different communities that they nevertheless ardently defended. And that’s indeed where all the paradox lied in.

The sixties constituted what we can call the golden age of idealism in the history of American youth. Never before had this many middle-class kids the time, energy and money to express their opinions. Their parents having insisted on the very importance of education to their future fulfillment, they would begin questioning whether what they learned in higher education establishments had any relevance with their lives, with their values and if the country was going in the right direction. The university being a microcosm of society, a large part of the students as well as some professors had an eye for this wishful fantasy that was revolution on campus which in one way or another would change this society which they considered rigid and oppressive.

On March 20, 1969, the strike ended. Joyous chaos and relaxed atmosphere still had the merit of obtaining the creation of a unique department devoted to Black Studies, an interdisciplinary field of research bringing together the historical, sociological, political and cultural study of the experience of Black people and guaranteeing the issue of a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.). Another major advance was the establishment of a School of Ethnic Studies, the first of its kind in an American university. The right of minorities to access knowledge and quality education on the reality of their community's experience was finally recognized.